Architects can make or break the style of any building, even your RFO house and lot. One of the best — if not the best — architects out there is our very own National Artist for Architecture, Leandro Locsin.

In this article, we’ll show you his life, most iconic work, and why his name resurfaced this year — even after 28 years since his passing.

PLDT petitions to remove RCB as an Important Cultural Property

The month of May is proclaimed as National Heritage Month by Presidential Proclamation No. 439 s. 2003. In the same month, last May 17, the National Commission for Culture and Arts (NCCA) broke the news that Philippine Long Distance Telephone (PLDT) Inc. petitioned to remove the Ramon Cojuangco Building (RCB) — the work of Leandro Locsin, a National Artist for Architecture — as an Important Cultural Property.

Photo from datacenterdynamics.com

RCB is located in Makati City, along Dela Rosa street corner Makati Avenue. It was designed by the national artist in 1974 and commissioned by PLDT Inc. (also called Philippine Long Distance Telephone Company at that time).

Now, according to the Republic Act No. 10066 or “National Cultural Heritage Act,” works of a national artist are presumed to be an Important Cultural Property. This means that the work is considered to possess exceptional cultural, artistic, and historical significance to the country. Moreover, this is considered to be second-level protection (the highest protection is given by the classification of National Cultural Treasures), so the work can’t be touched.

However, the law also states that the owner of the property is allowed to petition the appropriate cultural agency to remove the Important Cultural Property status. This led PLDT to file the petition to delist the building, on the following grounds:

- The RCB does not show exceptional historical, cultural, and artistic significance because it is nondescript, generic, and does not have any references to local culture and tradition.

- The condition of the building is considerably different from the actual distinctive style of the national artist, Leandro Locsin.

On top of this, last March of this year, a 60-page Technical and Heritage Assessment Report of the RCB was released by an independent architectural firm called Arc Lico International Services Corporation, a company headed by heritage conservationist and architect Gerard Lico.

The genealogy of Leandro Locsin’s architectural lineage was charted in the report and they found that the RCB does not represent the late architect’s work, as it deviates from his contemporary and original design elements. Hence, the RCB does not have architectural and stylistic rarity, physical integrity, technoscientific innovation, and the identity of the Filipino. Additionally, there are no associated historical and cultural events that took place in the building. It doesn’t have the scientific architectural innovation, method of construction, period style, and distinctive type that Leandro Locsin had in his other works.

After this report was released, PLDT sent its petition to the NCCA last April 4, 2022, where they cited the grounds that the architectural firm mentioned. They also mentioned that they intend to redevelop and transform the RCB into a more ecologically sustainable and modern headquarters.

Making major changes to the building is a huge deal to the company because it is their main office and they can’t touch it because of its Important Cultural Property status. Hence, the NCCA conducted an ocular assessment last May 5, 2022, and explained the processes required for the petition.

During the assessment, the NCCA mentioned the main changes of the building, which mostly involved interiors, fixtures, exterior paint, and flooring. Finally, they said that the floating effect characteristic of the floating planes of the exterior of the RCB is a distinct factor of Locsin’s language. The NCCA concluded that while the RCB has had some changes, these were reversible, so the building still reflects Locsin’s work.

While there is no verdict yet, the NCCA must wait for a written opposing petition until June 7, 2022.

Now, if you were PLDT and you own an RFO house and lot that you want to renovate but can’t because it’s preserved and protected by an Important Cultural Property status, what would you do?

Anyway, all this talk about Leandro Locsin’s work might have piqued your curiosity about the Filipino architect. So, let’s talk about his life and most famous works.

His Journey to Architecture

Leandro V. Locsin was born in Silay City, Negros Occidental on August 15, 1928. He went to De La Salle College (now De La Salle University) in Manila for elementary education but had to go back to Negros because of World War II. When it was safe, he went back to Manila to finish his secondary education in the same school and went on to study Pre-Law. However, he then decided to transfer to the University of Santo Tomas (UST) to pursue a degree in the Conservatory of Music, as he was also known to be very talented in playing the piano. In another twist in events, he then shifted to Architecture just a year before graduating.

Photo from ncca.gov.ph

His journey to becoming a national artist began with his love for art, as he’s a frequent visitor of the Philippine Art Gallery. In that same place, he met the curator, Fernando Zobel de Ayala, who then recommended him to the Ossorio family to build a chapel in Negros. Unfortunately, the plans for the chapel were canceled because Frederic Ossorio had to leave the country.

Still, his luck hadn’t run out.

In 1955, he was commissioned by then Diliman Catholic Chaplain, Fr. John Delaney, S.J. of the University of the Philippines to design a chapel that can accommodate 1,000 people. This chapel is now known as the Church of the Holy Sacrifice, which was the first round chapel in the country where the altar is situated in the middle and the first to have a thin shell concrete dome. The chapel is now considered a National Historical Landmark and a Cultural Treasure by the National Historical Institute.

Leandro Locsin then visited the United States where he met his influences, Eero Saarinen and Paul Rudolph. After learning everything he could, we went back to his home country where he was set to be commissioned for some of the most iconic buildings (no RFO house and lot, unfortunately) for both architectural and interior design.

Leandro Locsin’s most iconic works

The architect is known to have practically designed Makati City because he was commissioned for most of the buildings there, namely Ayala Building 1, Commercial Credit Corporation Building, J.M. Tuason Building, Ayala Museum, Ayala Triangle Tower One, Philippine Stock Exchange Plaza, and even then Ayala Avenue Pedestrianization Underpass. As majestic as these buildings look, here are some of his most iconic works:

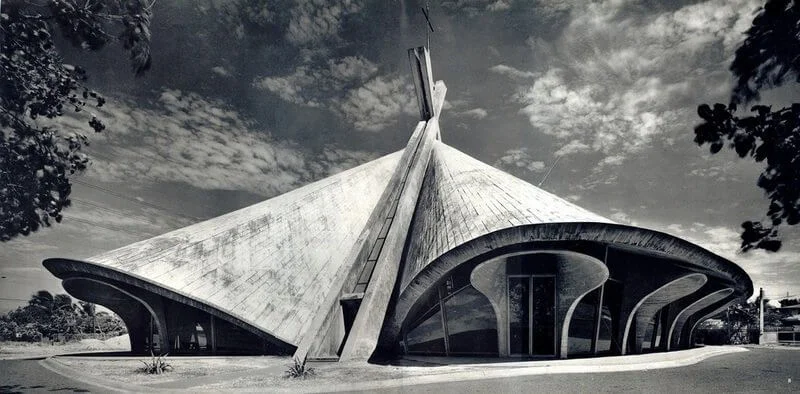

Saint Andrew the Apostle Church

The Saint Andrew the Apostle Parish is a Roman Catholic Church in Makati. The proposal for the church started in 1965 when a group of residents in Bel-Air, Makati wanted a parish for their village. Who wouldn’t want a church near their RFO house and lot, right?

Photo from twitter.com/MASContext

Don Andrés Soriano Jr., a Spanish-Filipino businessman and chief executive of San Miguel Corporation at that time, offered to have the church built in honor of Don Andres Sr., his father. Hence, the patron saint of the parish was chosen to be St. Andrew the Apostle, because it was the namesake of the patriarch.

Meanwhile, the Ayala family, through the Makati Development Corporation, donated a 3,494-square-meter lot where the church will finally stand and welcome the public on November 30, 1968. Since the lot was donated by the Ayala family, it comes as no surprise that they would commission their friend and esteemed architect, Leandro Locsin.

He designed the church as a symbolic way of how the martyr, St. Andrew, died by crucifixion on an X-shaped cross. This explains the butterfly-shaped floor plan. Moreover, other symbolic features include its sleek tent-like structure and a giant chandelier that serves as a halo hovering above the copper cross (which was created by another National Artist, Vincente Manansala).

Immaculate Heart of Mary Parish

Photo from bluprint.onemega.com

The Archbishop of Manila in 1964 wanted to divide the Sacred Heart of Jesus Parish in Quezon City because it was too large for just one parish. The area spanned between Quezon Avenue and EDSA QC. They wanted to divide this area between north and south, where the southern part will remain part of the Sacred Heart of Jesus Parish and the northern area will become the now Immaculate Heart of Mary Parish

Two years later, in 1967, the Claret School of Quezon City stood in the UP Village property of the Claretian Missionaries. The auditorium of the school was converted into a small chapel just so they can have daily masses until an actual parish church can be built.

Then, in September 1969, the area was inaugurated as a unit of the Archdiocese of Manila. The esteemed architect, Leandro Locsin, was then commissioned to conceptualize and design a church in the same year to accommodate the growing number of residents in Teacher’s Village.

Check Out Our House and Lot Properties in the South!

Locsin’s concept was inspired by the Filipino native hat called the “salakot,” which is symbolic as the church will be dedicated as a monument to the Filipino right in the heart of Quezon City. The interior matches the majestic exterior of the church, as the ceiling is in a spiral pattern like the weaving patterns of the salakot with Locsin’s signature manipulation of concrete.

The roof is designed to capture natural light so that it radiates throughout the church while creating a spotlight effect on the altar. Of course, you can also expect the floating effect, enclosed openness, grounded flight, and alternation of opposite spatial characters — all of which are known to be the signature of Leandro Locsin.

Sculptures inside the church were created by another national artist, Napoleon Abueva. You can see the intricate wooden reliefs of the stations of the cross at the peripheral of the church interior.

On December 10, 2018, Fr. Antonio Eucapor filed a petition to declare the Immaculate Heart of Mary Parish as an Important Cultural Property, which was then granted by the NCCA on July 30, 2019.

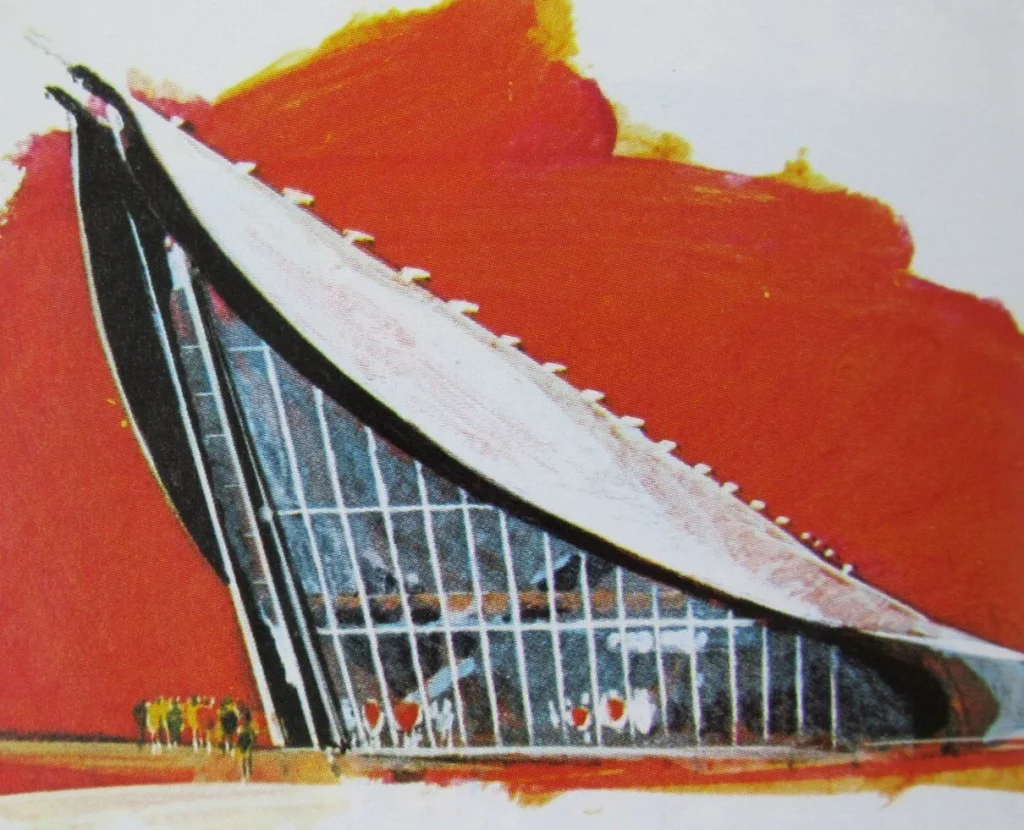

Expo ‘70 Philippine Pavilion

Photo from twitter.com/MASContext

Expo ‘70 was a world’s fair in Suita, Osaka Prefecture, Japan in 1970 with the theme “Progress and Harmony for Mankind.” This was the first-ever world’s fair held in Japan. The Expo had numerous pavilions and was practically an opportunity for countries to flex their architectural prowess to the world.

The pavilions were as follows: the Canadian pavilion (designed by architect Arthur Erickson), the West German pavilion (designed by Fritz Bornemann), the USSR pavilion (designed by Soviet architect Mikhail V. Posokhin), the US pavilion (designed by two architectural firms), Netherlands pavilion (designed by Carel Weeber and Jaap Bakema), the Hong Kong pavilion (designed by Alan Fitch, W. Szebo & Partners), and finally, the Philippine pavilion.

Of course, our pavilion was designed by non-other than Leandro Locsin, who was committed to making a strong architectural statement even with a limited building budget. He was worried that our pavilion might be overwhelmed by its neighbors, as the large mirror-wall pyramid of the Canadian pavilion rested right in front of ours.

He designed a dramatic roof that sweeps up from the ground to symbolize the soaring prospects and progressive spirit of the Filipino people. Hardwoods and other native materials were used for the pavilion. A narra planking on the ceiling was designed to direct the eyes to the top. Capiz shells were used as panels for the skylight which was designed to produce warm natural light for the interior.

Although small, the Philippine pavilion was one of the most popular pavilions at the event. On top of that, our country also won the title of Miss International, which had a coronation at the Expo ‘70.

Cultural Center of the Philippines

Photo from culturalcenter.gov.ph

Probably the most important cultural contribution of Leandro Locsin was the 88-hectare Cultural Center of the Philippines (CCP) Complex. It is comprised of numerous buildings, including the Folk Arts Theater, Coconut Palace, Film Center, and the Philippine International Convention Center.

Leandro Locsin designed these buildings with his signature floating effect. The CCP Complex is also clad in concrete textured with crushed seashells and marble.

All of the buildings also follow an international architectural style, including a square or rectangular footprint, simple cubic “extruded rectangle” form, broken horizontal rows of windows, and 90-degree facade angles — symbolizing the goal of the complex to showcase Philippine arts and culture to the world.